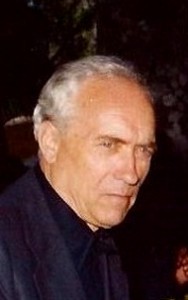

Manuel Faria In Focus in May

Manuel Faria (1916-1983)

Composer, teacher, conductor, journalist and lecturer, Father Manuel Faria was one of the more significant ecclesiastical figures that devoted himself to composition in the twentieth century in Portugal.

Born in Minho, in São Miguel de Seide in 1916, Manuel Faria has always maintained a close relationship with the popular music of his region. Music was instilled by his father, a concertina player that participated often in a popular singing group. Manuel Faria attended the archdiocesan seminary of Nossa Senhora da Canceição, in Braga, where he studied music with Father Alberto Brás, with Manuel Alaio and Antonio Domingues Correia. He was ordained priest in 1939. After the theology course, he went to the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music (P.I.M.S.) in Rome, studying with abbot Suñol, Rafael Casimiri (Polyphony), Licinio Recife (composition), among others. There he graduated in Gregorian Chant and Composition in 1943. In 1944 he obtained the degree of Magisterium in Sacred composition and presented his compositions at a concert in Rome in 1945. The works interpreted by the Choir of Radio Rome, in a concert that got recognition by the Italian music press.

After returning to Portugal he was appointed professor of Braga Conciliar Seminary where he was very active in teaching, choral conducting, and religious musical entertainment, besides composition and music criticism. Amílcar Vasques Dias, a composer who was a student of Manuel Faria, highlights the importance that the teacher had in his understanding of harmony: "He was particularly important in my listening training in harmony because he asked me to copy the parts of the scores of many of his choral works. The copy of the 4 male voices of the choir was an exercize that marked my ability for harmonic perception. "(Dias, Amílcar Vasques, interview published by MIC.PT, 2003, at www.mic.pt)

Manuel Faria was engaged in renovating liturgical music, and was concerned with the lack of quality in the music that was practiced and heard in the Church. According to the researcher Cristina Faria, "to a more practical level, the will of Manuel Faria to interfere with Portuguese liturgical music arose when we began to celebrate the Eucharist in Portuguese instead of Latin. Incidentally, one of the first Masses written in Portuguese is his own. The melodies are simple but we have the most complex accompaniments. "

His passage through Paris on his return to Portugal, has also contributed to making him an admirer of the French composers of the twentieth century. Curious and looking for new experiences, Manuel Faria tried to instill a spirit of renewal in the parishes in the North, considering that, "before being liturgical, music has to be music." He rehearsed gregorian chant in the Cathedral of Braga and tried to create new liturgical choirs, never neglecting his composer facet, both in sacred music and in chamber music. In 1949, the author of Cânticos Litúrgicos prepared at the Crystal Palace in Porto, a concert directed entirely by himself and dedicated to the presentation of his works, from motets "modern style" to the works devoted to choir and chamber orchestra. His music was known in Austria, the country where he has been for some time, and his Missa em Honra de Nossa Senhora de Fátima has been recorded by Radio Vienna in 1956. The conductor Frederico de Freitas took his symphonic music to Bahia and Recife, Brazil, too.

Returning to Italy

In 1961, with a scholarship of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Manuel Faria returned to Italy to continue his musical studies. He studied with Vito Frizzi in Siena and Boris Porena and Goffredo Petrassi in Rome. Following these studies, he experienced the twelve-tone composition, particularly in piano pieces like the Nine small pieces for chamber orchestra (1961-65) and the Liturgical Triptych , for organ (1963). However, these were very brief and isolated experiments. André Vaz Pereira, a researcher at the University of Aveiro who studied the piano work of Manuel Faria, believes that the composer was "reluctant in relation to the twelve-tone technique". In the words of Manuel Faria himself: "the unique and systematic dodecaphonism is unconvincing for me. I have done some efforts, but I can not grasp its message. The music interests me, as a composer, for its novelty (that yes), but it does not touch my heart; And I am one of those people who ask art and especially music to give you an emotion, whatever it may be. "(Faria, 1961, quoted by Pereira, André Vaz, 2009). In a letter written to Frederico de Freitas and after hearing the Four Small Pieces for Piano, he stated: "after studying dodecaphonism I still don’t understand it (...) there is no way to force my sensitivity to accept the cacophony ( ...) of Schöenberg and Webern. On the other hand, I like the full beauty of Berg and Dallapicola. (...) Some days ago I heard my three dodecaphonic pieces (strictly) for piano and I found them beautiful... So I do not know what to do. "(Faria, 1962, quoted by Pereira, André Vaz, 2009).

Between 1964 and 1967 Manuel Faria was president of the Braga delegation of Portuguese Musical Youth. From 1967 he was president of Bracarense Commission of Sacred Music, a position he held until the end of life. There he developed various activities related to the promotion, study and dissemination of religious music, organizing the Weeks of sacred music, choirs meetings and choral conducting courses. He taught in the diocesan seminaries of Braga and was responsible for the music in the Cathedral of Braga. In 1967 he took over as leader of the Basilica. In 1971 he won the National Composition Prize "Carlos Seixas" given by the State Department of Information and Tourism.

In his attempt to start a renewal of liturgical music, Manuel Faria also had a theoretical intervention, through written texts and conferences in the New Journal of Sacred Music. For the composer, the music should serve to uplift the spirit. Manuel Faria has also acted as an animator of several movements including the creation of popular choirs and organ courses for amateurs of villages. He started a Harmony free course for students of Humanities, Philosophy and Theology in the Seminar.

Cristina Faria says Manuel Faria acted "in several ways: writing, preaching at various locations, and making music, rehearsing with local choirs, and this way leaving his seed." (Interview conducted by researcher Maria Leonor Barbosa de Melo , in Melo, Barbosa, 2015)

The religious, the popular and other influences

Manuel Faria has a vast work, with more than 500 pieces. Much of his production as a composer has been devoted to music for choir a cappella and choir with instruments. His first compositions date back to the '30s, in which he writes several songs and pieces for chorus and the first pieces for piano. In 1935 he composes the O Barbosa foi ao mar, a work for piano where said to have "confessed" to the piano "the love I have for our people and for our land" (Faria, Manuel, 1955, quoted by Pereira, André Vaz, 2009). Gradually his work for piano reveals, according to André Vaz Pereira, the influence of Portuguese composers (especially Luis de Freitas Branco and Frederico de Freitas) but also of French composers such as Claude Debussy. In this compositional aspect, Manuel Faria stated that "we have a clearly individualized popular song, with its roots (...) in (...) troubadour song and it had a profound influence in the music renewal of the first half of this century" (Faria, Manuel 1961 quoted by Pereira, André Vaz, 2009). In Four small pieces for piano of 1961, the composer reveals knowing the pieces of Schoenberg for piano. However, rather than to look for references in other composers, Faria defended the knowledge and use of the popular Portuguese musical heritage: "As for the integration of existing composers in this popular tradition, I do not really see another way out. If in the past we lack 'big names’ it is precisely because we were looking more for the outside than the inside "(Faria, Manuel, 1961, quoted by Pereira, André Vaz, 2009).

Among his early works for piano are Fantasia Brilhante (1934) and the Funeral March (1941). Vaz Pereira highlights the "harmonic boldness" of his compositions soon since the 40’s, influenced by impressionists, for instance in the using of an ostinato in the left hand that takes us to some

Preludes of Debussy, such as the Sunken Cathedral (preludes that

Manuel Faria knew), in which the melodic speech in 7th successive chords is accompanied by a "mist" sound. "

Manuel Faria may have also been influenced by other Italian and French composers, in particular by Luciano Berio (1925-2003) and one of his teachers, Goffredo Petrassi (1904-2003), or even Jean Langlais (1907-1991), which focused large part of his work in Gregorian chant. According to Vaz Pereira "modal language has evolved into a more complex sound, even using twelve-tone." However dodecaphonism was never his language. A piano piece from 1948, Adeus, "shows a certain distance of tonal music and shows a different direction with respect to the composer's language. Manuel Faria had a special appreciation for post-romantic music and modern French music, which was "imported" by Portuguese composers. This small piece shows clearly the importance of composers such as Luis de Freitas Branco, Marcel Dupré, Darius Milhaud, Claude Debussy and Gabriel Fauré had in the Portuguese musical production of the time "(Pereira, André Vaz, 2009).

Musical features

Manuel Faria was interested in folk music, something evident in his harmonizations of popular songs, which are his most frequently performed pieces. Vaz Pereira, citing Manuel Faria: "In the article "Popular Music and Classical Music" (...) the composer refers to himself as a man of the people: 'I can not speak of popular song without speaking of me' (Faria, undated notes). The composer goes even further in this regard stating that: 'Folk music has for me the same importance as the land where we were born, the family where we grew up, as education that guided us in the first steps in the ways of the world'" (Faria, notes without date).

Jorge Alves Barbosa, a priest who worked closely with Manuel Faria says that he wanted "to give sacred music its popular flavor, using popular themes, as in the Missa de Nossa Senhora do Sameiro, the most popular of all, that integrates, conscious or unconsciously, a theme from the song No alto daquela serra, which also gives a theme to Suite Minhota. The titles and themes of the songs, right from the earliest times, have a popular flavour. "

In addition to religious music Manuel Faria was also composing music of other kind, having written, for example, a set of twenty-three songs for voice and piano.

Nevertheless, the vast majority of his compositions are of religious nature and influenced by the texts and the religious contexts. He wrote dozens of masses, songs, religious works for small and medium vocal ensembles, works for soloist and instrument, motets, etc. According to Cristina Faria and António José Ferreira, his vocal style "reflects the influence of northern popular music."

Jorge Alves Barbosa believes that "in his music we can hear some predilection for descriptivism, madrigalism or mannerism if you want. This is present even in his sacred music." Cristina Faria also refers to this "descriptive " aspect of his music, even in instrumental works: "His instrumental music is predominantly figurative, even approaching programmatic music, without however reaching it, as can be seen in his works for symphony orchestra like Suite Minhota, Imagens da minha terra or Jacob e o anjo "(Faria and Ferreira, 2010). In 1963 Manuel Faria composed an opera commissioned by the Coimbra City Council for the ninth centenary of the conquest of Coimbra from the Moors: Auto da fundação e conquista de Coimbra.

Simple melodies, complex harmonies

Among the dominant features of his music, several authors refer to the use of ostinato, his way of searching expressiveness above all, always closely linked to the word and the religious texts.

Jorge Alves Barbosa also reflects about the melodic and harmonic characteristics of Manuel Faria: "He tried, at the end of life, a more modal flavor of language, but did not affirm it with consistency (...). From the harmonic point of view, he cultivates dissonance with particular frequency and intensity, particularly in the instrumental accompaniments; sometimes he is a little inconsistent from a stylistic point of view, (...) as if he followed his fantasy more than searching for a language coherence or a particular harmonic system.” (Jorge Alves Barbosa, interview conducted by researcher Maria Leonor Barbosa de Melo, in Melo, Barbosa, 2015)

Cristina Faria, niece of Manuel Faria and author of a thesis on his uncle, speaks of his vocal work: "There are many choirs singing harmonies made by him but few can perform his original works, whether sacred or profane, because the degree of difficulty is high. Manuel Faria was an accomplished pianist and an accomplished tenor, and that's why, for example, tenor voices are so high and so hard to sing. We must remember that even Manuel Faria wrote much of his music in the seminary with the voices of the seminarians he had at his disposal. At that time the seminars had a lot of people, enough men for writing the parts for four different male voices."(Interview conducted by researcher Maria Leonor Barbosa de Melo, in Melo, Barbosa 2015)

The word and the music

Manuel Faria was an important composer of the twentieth century in Portugal, committed to the renewal of liturgical music. His work deserves to be better known. Manuel Faria has always given special attention to the word, and the link between the word and music. Composer of simple melodies (often with popular flavor) on sometimes complex harmonies, its harmonic language sought the maximum expressiveness and, at the same time, the perfect symbiosis between text and music. Curious and intuitive composer, living all his life between music and religion, Manuel Faria found his voice precisely the encounter between text and music.

The musical work of Manuel Faria is largely deposited in the section of musical manuscripts of the General Library of the University of Coimbra. A small part is kept in the Conciliar Seminary of Braga.

References:

Bartocci, Aldo (1984) “Manuel Faria no P.I.M.S.” in Nova Revista da Música Sacra.

Ano XI, 2ª série, nº31 (p.2);

Branco, João de Freitas (2005, 4ª edição actualizada; 1959) História da Música

Portuguesa. Lisboa: Europa América;

Brissos, Ana Cristina, Manuel Faria (1916-1983), in MIC.PT – Centro de Investigação e Informação da Música Portuguesa (www.mic.pt);

Carvalho, Joaquim Azevedo Mendes de (1992) Vida e obra de Manuel Faria. Vila das

Aves;

Faria, Cristina e António José Ferreira, Manuel Faria, in Enciclopédia da Música Portugal no Século XX, INET/Círculo de Leitores - Temas e Debates, Lisboa, 2010;

Faria, Cristina (1992) Manuel Faria: vida e obra (Tese de Mestrado em Ciências

Musicais Coimbra): Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra;

Faria, C. (1998). Manuel Faria : vida e obra. (Tese de mestrado em Ciências

Musicais apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra). Vila Nova

Famalicão : Câmara Municipal V. N. Famalicão;

Faria, Francisco (1983) “A Música de Manuel Faria. A fidelidade ao espírito”, “catálogo

provisório das obras de Manuel Faria” in Nova Revista da Música Sacra 2ª série (27-

28) (pp. 1-7);

Faria, Manuel (1955) “Carta Aberta ao Sr. Querubim Guimarães” in Diário do Minho.

Braga;

Faria, Manuel (1961) Entrevista a Manuel Faria in Gazeta Musical e de Todas as

Artes. ANO X, 2ª Série nº 126/127;

Faria, Manuel (1964, Junho) “Francis Poulenc: musicien français” in Praça Nova.

Lisboa;

Faria, Manuel (1960, Junho) “Música de laboratório” in Praça Nova. Lisboa;

Faria, Manuel (1963, Março) “Nasceu Há Cem anos o Primeiro Músico Moderno

(efeméride a Debussy)” in Praça Nova. Lisboa;

Faria, Manuel (1962) “No centenário do nascimento de Gustav Mahler” in Praça

Nova. Lisboa;

Faria, Manuel (1965) Para onde caminha a música. Braga: Edições Cenáculo;

Faria, Manuel (1963) “Pedro de Freitas Branco” in Praça Nova. Lisboa;

Faria, Manuel (1976) “Morreu o Senhor Padre Brás” in Diário do Minho, Braga;

Faria, Manuel (1977) Beethoven – compositor católico. Braga: Separata da Revista

Cenáculo;

Faria, Manuel (sem data) “Música Popular e Música Erudita” Espólio literário de

Manuel Faria;

Faria, Manuel (sem data) “Olivier Messiaen – Compositor católico” Espólio literário

Manuel Faria;

Faria Manuel (1949) “Comemoração do centenário de Frederico Chopin” Espólio

literário Manuel Faria;

Martins, Celina Teixeira (2008) O tríptico para órgão de Manuel Faria no contexto do

repertório organístico do século XX, Tese de Mestrado, Departamento de

Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro;

Melo, Maria Leonor Saraiva Barbosa de (2015), A obra integral para canto e piano de Manuel Faria, Dissertação de Mestrado em Performance Musical, Universidade Católica do Porto;

Monteiro, António Xavier (1983) “Dr. Manuel Faria in memoriam” in Nova Revista da

Música Sacra. Ano X, 2ª série, nº26;

Pereira, A. (2009). Manuel Faria e o piano (das fontes primárias à performance). - Dissertação de mestrado não publicada. Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro;

Simões, Manuel (1984) “Homenagem ao Compositor Manuel Faria na sua terra” in

Nova revista de Música Sacra. Ano XI, 2ª série, nº31 8 (p.1)